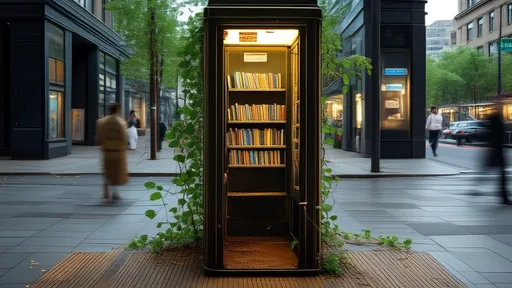

In an age where smartphones dominate communication, the sight of a red telephone booth in Britain—or its equivalents elsewhere—often evokes nostalgia. Yet, some of these relics of the 20th century have found new life as micro-libraries, transforming into unexpected hubs of community interaction. These repurposed booths are no longer just storage spaces for forgotten phone directories; they’ve become neural nodes in the cultural ecosystem of neighborhoods, stitching together collective memory and contemporary creativity.

Walking through the streets of London’s suburbs or rural villages, one might stumble upon a phone booth crammed with paperbacks, their spines facing outward like colorful tiles. The books range from dog-eared classics to contemporary bestsellers, often accompanied by handwritten notes left by anonymous contributors. Unlike formal libraries, these spaces operate on an honor system—take a book, leave a book, no deadlines, no fines. The simplicity of the exchange belies its deeper significance: these booths are living experiments in trust and shared ownership.

What makes these structures particularly fascinating is their dual role as physical and symbolic landmarks. On one level, they serve as book exchanges, but their impact extends beyond literacy. They act as accidental gathering spots, where neighbors pause to browse titles and strike up conversations. In an era of digital isolation, the phone booth library forces a momentary deceleration—a chance encounter with both literature and community. The very act of opening the creaking glass door becomes a ritual, a small rebellion against the impersonality of algorithmic recommendations.

The aesthetics of these installations often reflect the character of their surroundings. In artsy districts, booths might be painted in psychedelic patterns or fitted with miniature chandeliers; in coastal towns, they’re lined with seashells and nautical novels. Some host seed exchanges for gardeners, others become galleries for local artists. This adaptability reveals how communities imprint their identities onto utilitarian objects, converting infrastructure into folk art. The phone booth, once a symbol of top-down urban planning, is now a canvas for bottom-up cultural expression.

Critically, these projects thrive on what urbanists call "loose space"—underutilized areas that citizens reclaim for unplanned purposes. Unlike designated cultural centers, phone booth libraries emerge organically, often through grassroots initiatives. A retired teacher stocks the first shelf; a teen book club adopts weekly maintenance duties; a neighborhood association funds weatherproofing. The lack of institutional oversight becomes an asset, allowing for quirky, hyper-local customization that official programs rarely permit. In this sense, the booths function as cultural petri dishes, where small-scale experiments in communal stewardship can flourish.

The phenomenon also highlights a paradox of our digital transition: as society becomes more virtual, the hunger for tangible, place-based connection intensifies. Social media groups might facilitate book swaps, but they lack the serendipity of discovering a rain-warped Agatha Christie novel while waiting for a bus. The tactile experience—the smell of aging paper, the sound of flipping pages—grounds these exchanges in physical reality. Notably, many booth curators deliberately exclude e-books, emphasizing materiality as antidote to screen fatigue.

These structures also serve as quiet monuments to urban evolution. The phone booth’s original function—providing private communication in public space—has been rendered obsolete by mobile technology. Yet its reincarnation as a library repurposes privacy for a new era: the booth becomes a sanctuary for solitary reading amid the city’s chaos, or a stage for impromptu story hours where children cluster on the threshold. The architecture itself, designed for acoustic isolation, now amplifies cultural resonance.

Perhaps the most subversive aspect lies in their resistance to metrics. Unlike digital platforms that quantify engagement through clicks and downloads, phone booth libraries operate outside surveillance capitalism. No data is collected on which books move fastest; no algorithms optimize selections based on borrowing patterns. Success is measured anecdotally—through the gradual accumulation of marginalia, the lengthening waitlist for popular titles, or simply the persistence of the booth itself as a neighborhood fixture. In this, they model an alternative economy of cultural exchange, one driven by use-value rather than analytics.

As climate change accelerates, these micro-libraries also demonstrate adaptive reuse at its most pragmatic. Rather than demolishing energy-intensive structures, communities retrofit them with minimal carbon footprint. Solar panels power nighttime lighting; salvaged materials build weather guards. Some booths even incorporate "little free pantry" sections, addressing food insecurity alongside literary access. This multidimensionality turns each installation into a local syllabus on sustainability, teaching through hands-on example rather than didactic signage.

The movement isn’t without challenges. Vandalism, weather damage, and bureaucratic hurdles test organizers’ resolve. Yet the very fragility of these projects—their dependence on ongoing communal care—is what makes them culturally significant. Like a neighborhood garden or a mural project, their survival requires continuous negotiation between strangers. The phone booth library becomes not just a repository of books, but of social contracts, its contents mirroring the evolving compromises of shared space.

In global cities from Berlin to Tokyo, variations on this theme continue to proliferate, each adapting the concept to local needs. The underlying principle remains: when given agency over public artifacts, people will invent modes of connection that formal institutions seldom imagine. These glass-and-metal capsules, once designed for transient calls, now transmit something more enduring—the quiet pulse of community inventiveness, one dog-eared paperback at a time.

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025

By /Jul 8, 2025